|

The designated hitter is coming to the National League this season, marking the first time baseball’s Senior Circuit will fail to see pitchers put up their collective .120/.120/.120 line. That should tell you where my opinion stands on the matter.

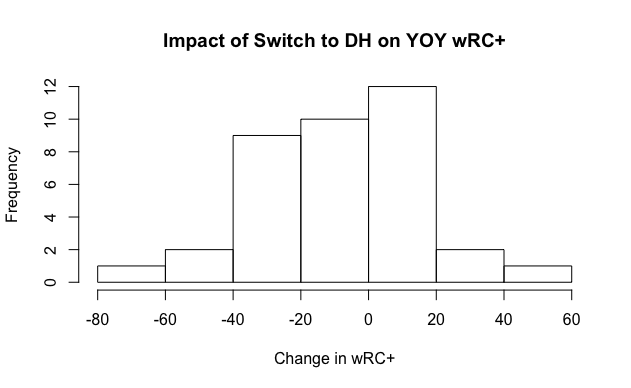

Because this rule change was rather abrupt (and may only be for the 2020 season regardless), teams in the National League did not get the opportunity to construct their roster accordingly. They did not go into an offseason where they could target specific free agents to serve as their DH. Rather, they have to deal with the players currently on their roster, unless they want to make a last-ditch effort to fill this role now that transactions are unfrozen. Either way, as a result, they are left at a significant disadvantage when compared to their American League counterparts. At a minimum, this quirk gives NL teams some options. For a team like the Dodgers, which seemingly has an entire roster full of starting-caliber bats, flexibility is added. For the Nationals, Howie Kendrick has an opportunity to play more often. For the Mets, this could mean a return of Yoenis Cespedes for the first time since 2018. When each team sits down to consider plans for their DH slot in 2020, one important question will need to be asked: Should we make the DH position a permanent starting spot, à la J.D. Martinez and the Red Sox, or should we rotate the position to allow players de facto “days off” while keeping their bats in the lineup? Considering what I said above about NL teams’ inability to plan for this shift in the rules, the general answer is pretty clearly the latter: Use the DH as a rest spot. But that’s not the end of the story. Let’s consider what exactly makes this the obvious answer. First, there’s a question of player value. Players who spend an entire season at DH lose significant value as a result of never playing the field. The positional adjustment is -17.5 runs over 162 games, or -6.48 runs over 60 games. That means, without adjusting for park factors and without considering potentially added value from base running, a full-time DH needs to post at least a .354 wOBA in order to break even over 600 PA. Automatically, that requires them to be at least a 60th percentile hitter. It’s not a surprise that a DH would need to hit better in order to capture some of the value they lose from not playing the field. What’s more of a surprise, however, is what happens when a player goes from playing the field one season to being primarily a DH the next. Since 2010, there are 37 individual player-seasons that fit this criteria, representing a player who played more than 50 percent of his games in the field one year and then more than 50 percent of his games at DH the next. In all 37 cases, it was not a 51-49 to 49-51 switch; these all represented pretty substantial movements. Shin-Soo Choo’s “move” from 2017 to 2018 was the smallest switch by far; 46% of his appearances in 2017 were at DH compared to 59% in 2018, a 13-percentage point movement. Generally speaking, though, 32 of the 37 player-seasons represented movements of at least 40 percentage points, and 24 of them represented movements of at least 50. These are rather large movements from non-DH’ing to DH’ing. The results were interesting. Twenty-two of these players — or roughly 60 percent — experienced a year-over-year decrease in wOBA and wRC+. The median decrease in wOBA was 14 points; the average was 15. The median decrease in wRC+ was 7 points; the average was 8.7 points. Here’s a histogram demonstrating the impact of a switch to DH on year-over-year wRC+: To be fair, this is a rather back-of-napkin approach. There is admittedly quite a bit of bias in this study. It does not control for age, percentage of time spent at DH, and does not attempt to decrease general year-to-year randomness. It is simply an observational look at what happened to players who spent less than 50 percent of their time at DH one season and more than 50 percent of the time at DH the next. What’s encouraging about these results, though, is that they align with prior, more detailed studies. Perhaps coincidentally, the 14-point median decrease in wOBA is exactly what was explained as the “DH penalty” here, in an analysis of baseball’s “penalties.” The logic behind it makes sense: Players might hit worse if they're less involved in the game. Though the data in my quick look may be rather raw, it does fit in with the larger trend. Assuming that 14 points is indeed the DH penalty, some revision must be made to the earlier math. While a hitter does need to post a .354 wOBA to “break even” as a DH, we now have to work in the penalty. Thus, through this logic, you would need a .368 true-talent wOBA hitter in order to have an effective full-time DH. Among qualified hitters last season, that would mean that this Player X would have to be at least a true-talent 73rd percentile hitter for a switch to full-time DH to be effective. (This assumes that the DH penalty impacts all hitters identically, which is almost certainly false.) The math clicks further when evaluating real-world examples. J.D. Martinez is an excellent full-time DH, but that’s because his wOBA since his breakout year has hovered near .400. Nelson Cruz, too, makes the spot work; since his first season playing DH in at least 100 games, he has a .385 wOBA. (And, remember, these examples are presumably with the penalty included.) But this is all to say that National League teams likely do not have a .368 true-talent wOBA hitter laying around somewhere, or even a player who has fit inside the .354 wOBA DH threshold. Two prime candidates to receive a considerable portion of National League DH plate appearances, Hunter Pence and Howie Kendrick, were the only listed “starters” (defined by me as the player with the most PA at the DH spot) on the FanGraphs Depth Charts to post a 2019 wOBA above .368. If we expand the baseline to .354, we have six names: Ryan Braun, Nick Castellanos, Kendrick, Joc Pederson, Pence and Kyle Schwarber. But again, that’s only to break even as a full-time DH, and that doesn’t even account for the penalty. Plus, for someone like Kendrick, playing DH might be a way to get him more plate appearances, yes, but he’s not an awful defender either. Last season, he rated positively in small samples at second and third base, and just a touch below-average at first. That is yet another consideration these teams must make when answering this question: Is this player even that big of a liability defensively anyway? All of this is to say one thing: For NL teams this year, the DH should be used as nothing more than a rotating off-day. The offensive and defensive downside associated with playing one player in that slot the entire season is likely too much to overcome, especially when these teams did not have an offseason to prepare for this abrupt rule change. Given more time to adjust, I think we could see the gap between the two leagues close, but this year, the idea of the “full-time designated hitter” should be left to the Junior Circuit only. — Devan Fink

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed