|

Baseball is going to look different this year for a host of reasons, but one change that was coming — pandemic or not — was the three-batter minimum rule for pitchers.

Officially implemented at last year’s Winter Meetings in San Diego, pitchers who enter games this season will be required to face a minimum of three batters or pitch to the end of a half-inning, with exceptions due to injury or illness. The rationale behind this change is to limit the number of mid-inning pitching changes, in hopes of shortening the length of games. Critics ripped the rule change for eliminating strategy, while others pointed out that baseball’s strategy would be merely different. “I think it’s good for baseball,” Diamondbacks manager Torey Lovullo told Forbes in February. “It’ll keep the game moving. It’ll possibly create a little more offense. You’re going to be able to stack your lineup a certain way to get the matchup you want to get. There’s more creativity and strategy to it and I always like that.” Part of the new creativity is to evaluate relievers’ performance against batters of both handedness. Dominant pitchers such as Kirby Yates will hardly be impacted — Yates allowed a .245 wOBA against lefties versus a .208 wOBA against righties — but left-handed one out guys (LOOGYs) could become a thing of the past. Unless, of course, they can actually get out batters of both handedness.

The question of pitching changes becomes deeper in 2020, and, like all else, more important. As Jon Weisman tweeted earlier this week, each blown save this year is three times as significant as in years past, given the condensed schedule. For managers, bullpen management will need to be especially shrewd.

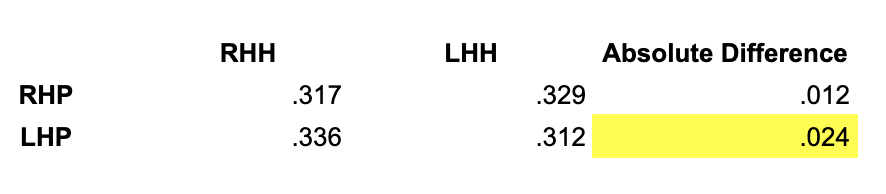

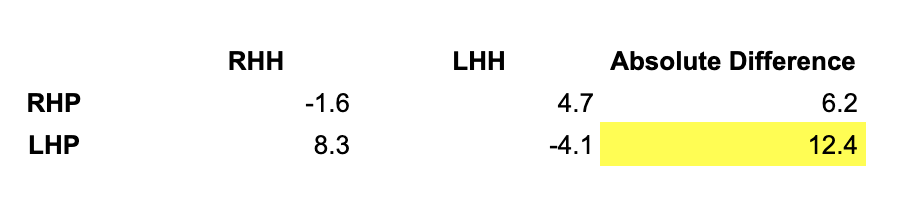

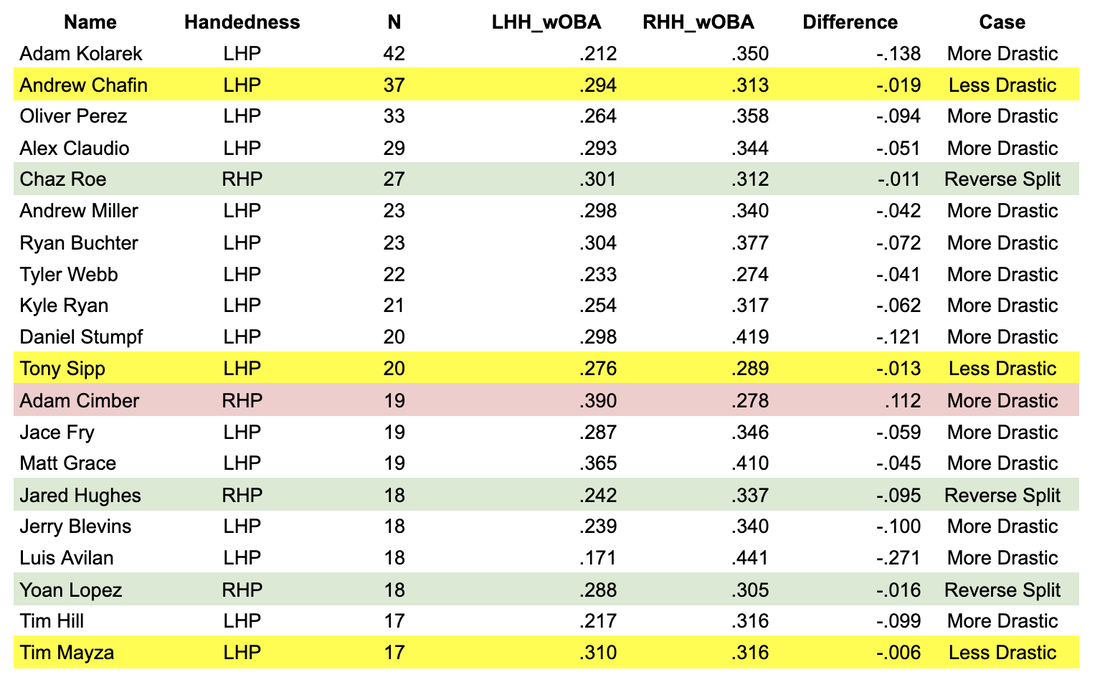

Is the LOOGY dead, though? Maybe not. I was debating an interesting question with my friend a few days ago: On a percentage basis and compared to 2019, will we see lefties throw more or fewer pitches in 2020? We both agreed that the answer was probably more, with my reasoning being that since left-handed hitters (.326 non-pitcher wOBA) tend to be slightly better than right-handed hitters (.324 non-pitcher wOBA), teams may opt for the consequences of having their lefty face a righty. Furthering this point, here are the handedness splits for non-pitchers from the 2019 season. The overall league-average wOBA for non-pitchers was .325: If a left-handed hitter is at the plate, putting a left-handed pitcher in the game offers you the highest benefit, a 13-point wOBA gain compared to the league-average. If a right-handed hitter is at the plate, leaving the left-handed pitcher in the game results in the worst cost, 11 points of wOBA. For right-handed pitchers, the platoon “spread” is much smaller, an 8-point gain versus a 4-point cost. Because right-handed pitchers offer the best ratio, a two-times larger benefit than the cost, that’s why we don’t really see any ROOGYs. Compared to the league-average hitter, an opposing batter being left-handed doesn’t automatically pose a huge challenge for a right-handed reliever. We cannot say the same for left-handed relievers. Working in terms of wOBA can be a bit abstract, so one way to better see the impact of the platoon advantage is through runs. If those four wOBAs in the above chart were batters with 600 plate appearances, this is how many runs above- or below-average they would have been on offense, without adjusting for park- or league-factors: What this is saying, for example, is that if an average right-handed hitter faced an average left-handed pitcher in each plate appearance of a 600-plate appearance season, his offensive production would be 8.3 runs above-average. It is pretty incredible to think about the fact that these differences are only the result of handedness overall because the platoon advantage can become much more important when facing individual hitters. Michael Conforto, for example, posted a .304 wOBA against lefties but a .382 wOBA against righties. Now what — how will teams handle this? First, it’s important to evaluate which pitchers had the most qualifying appearances. Though the exact wording of the rule issued would not impact pitchers if they faced only one batter to end an inning, these appearances were included in my dataset. I just wanted to focus on one type of relief appearance from 2019: those that included fewer than three batters faced. There were 2,162 such appearances last year, with 423 different pitchers having at least one. Here were the 20 pitchers with the most appearances spanning two or fewer batters: There’s a lot going on here, so let’s break it down: First, 16 of the 20 pitchers above are lefties, which passes the sniff test if the intention of this exercise was to find LOOGYs. Of the four right-handed pitchers, three of them had pretty drastic reverse splits. Jared Hughes, for example, saw his performance against the average lefty improve by 95 points of wOBA when compared to righties, even though he is a right-handed pitcher. Second, only three pitchers — Andrew Chafin, Tony Sipp, and Tim Mayza — saw a platoon difference that was less drastic than the league-average, again indicating that this list is mostly one of LOOGYs. If the split holds in 2020, these three pitchers should be fine facing batters of both handedness. (Chafin and Sipp have had relatively similar splits in prior years, though Mayza has a 73-point gap for his career.) Third, Adam Cimber. He’s the ROOGY on this list, and 2019 didn’t seem to be a one-year fluke, either. In 378 plate appearances, righties have hit just .241/.288/.339 (.207 wOBA) against him, compared to .315/.413/.598 (.407 wOBA) in 150 plate appearances for lefties. I’m not sure how the Indians plan to use him this year, but I would worry about leaving him to face too many lefties. Fourth, Luis Avilan. He is the holder of the most drastic platoon split on this list, and after joining the Yankees on a minor league deal in January, it’ll be interesting to see how New York decides to utilize him. Unlike Cimber, Avilan’s career split (.254 wOBA for LHH, .307 wOBA for RHH) isn’t awful, but it was pretty problematic last year. As alluded, some of these splits don’t hold up over time. It takes hundreds of plate appearances for “true-talent” splits to show up. If you think relievers are somewhat random on a year-to-year basis, think about how much randomness is induced after breaking down their performance into smaller detail. So, out of fairness to them, here are the career righty-lefty splits for these 20 pitchers:

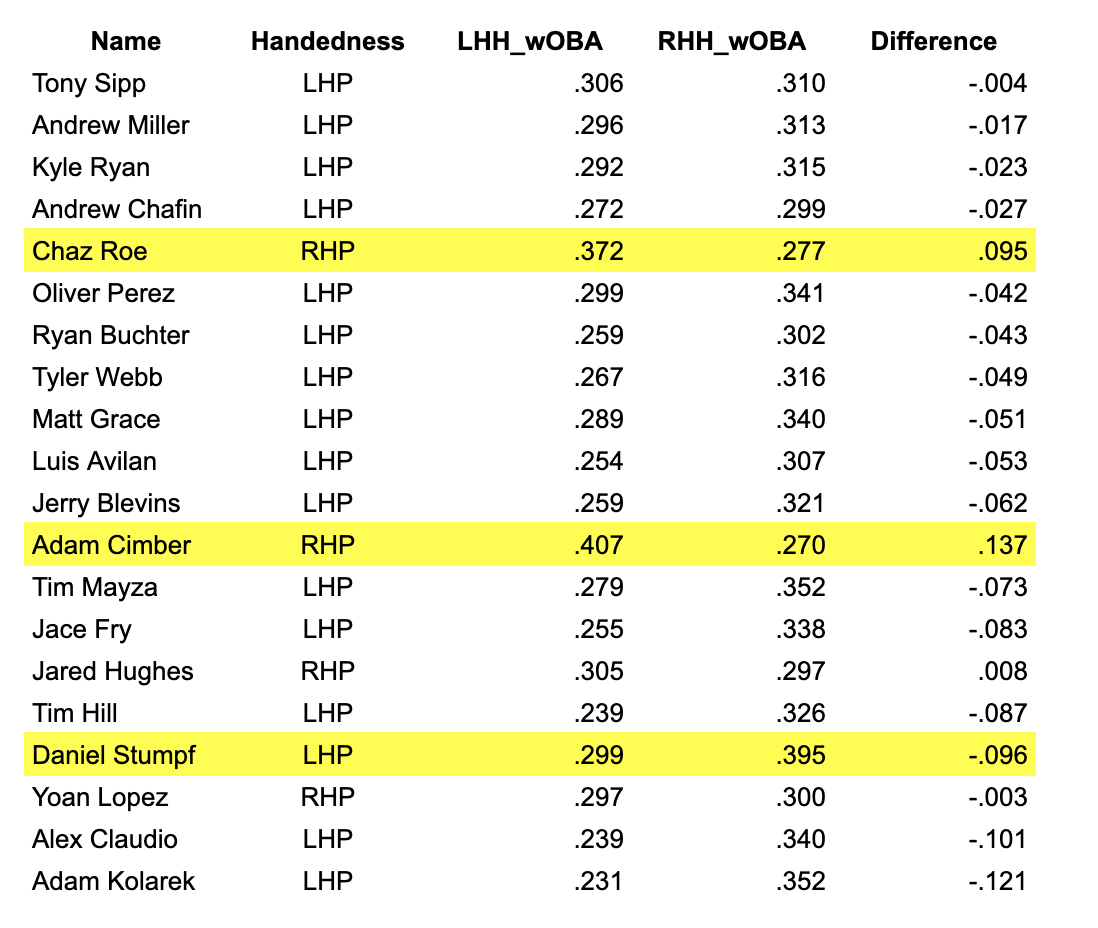

In this chart, the yellow highlight represents pitchers who allow a wOBA one platoon side that is worse than the 75th percentile 2019 wOBA, or .356. This is entirely an arbitrary number, though it suggests that a situation in which two of the next three hitters are platoon favorable might not yield an apocalyptic result.

Looking at these figures tells somewhat of a different story. Going back to our 16 left-handers, all of them have some advantage against left-handed hitters, though Miller, Ryan, and Sipp have a less drastic split than the 2019 average. The other 13 all generally suit the LOOGY role, but only Daniel Stumpf seemingly would be challenged to get a right-handed hitter out if sandwiched between two lefties. Interestingly, it’s two of the four righties that seem to pose a larger puzzle to their teams, the aforementioned Cimber and Chaz Roe. Roe played an important role in Tampa Bay’s bullpen last year, putting up 0.9 WAR, perhaps in part due to his limited exposure against left-handed hitters (76% of the batters he faced last year were right-handed). He had reportedly been working on a cutter to give him another weapon versus lefties. All told, yes, baseball is going to be different for a multitude of reasons this year. In a 60-game season, teams are going to have to develop strategies to adapt to a pennant race-only sprint. The three-batter minimum rule is surely going to throw an extra wrench into their plans, and with each blown save being three times as important this year, they’re going to want to ensure that they have the best pitcher in the game at all times. How each team handles its bullpen is going to be a major key to success, with the three-batter minimum surely being at the forefront of the minds of managers and the front office staff. —Devan Fink

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed